.

Cholera

This summary has been compiled following discussions with a former Curate of Broseley (1972-

Cholera arrived in Broseley in 1832. It was the result of one of the earliest identified pandemics which started in Bengal in 1826 and spread to Persia, Afghanistan, Russia and Western Europe by 1830. The first cases in Great Britain were reported in Sunderland in September 1831 after the port authorities failed to implement a directive to quarantine all vessels arriving from the Baltic. Surgeons thought it was transmitted by touch or from bad smells but there was no known cure. Symptoms started with giddiness, vomiting and diarrhoea. In many cases death followed in just a few hours. By November 1832, the disease had spread throughout the country, with over 52,000 fatalities.

In October 1831, ahead of the epidemic, an Order in Council recommended that Boards of Health should be set up in every town. The Broseley Board was established at a public meeting in the Town Hall on 28 November 1831. It included the Rector, Rev Townsend Forester, the three surgeons, William Fifield, Richard Thursfield and Richard Wyke; George Pritchard was nominated as Secretary. Broseley was divided into three districts, each under the control of one of the surgeons and every house inspected. Conditions in some houses were described as being “in a disgusting state and wretchedness” and many more were “unclean.”

At first, all went well and in February 1832, the Board was suspended as cholera had not been seen in the town. However, this was premature, the first cases being treated by Mr Thursfield on 11th July. Attempts were made to stop the disease by isolating the sick, burning the victims’ beds and clothes, painting the walls and roofs of the houses with lime wash and covering drains and sewers, where these existed. On 23rd July, a Mr John Griffiths was asked to build a special carriage to collect victims and corpses, some of the sick being taken to Calcutts House which effectively became an isolation hospital. Treatment appears to have included a variety of ill-

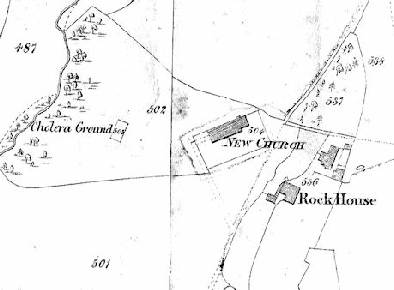

Site of the Red Church and the Cholera Burial Ground, Tithe Map 1838

Following a request from the Broseley Board of Heath, a piece of land 40ft x 20ft adjacent to the Red Church graveyard was given by the landowner, Francis Harries, for burials due to cholera as it was not thought “right” to use the main cemetery. The first burial recorded specifically in the Cholera Field is dated 18th August 1832. By October 1832, the epidemic subsided but at least fifteen burials had taken place in the Cholera Field. In that month, responsibility for care of cholera victims was reduced to just one medical person. The following year was free of burials and in June 1833, the Broseley Board of Health was dissolved. Unfortunately, this was ahead of a further outbreak in 1834 with twenty-

The 37 victims named in the Parish Registers underestimate the severity of the outbreaks. For example, the deaths in July 1832 were not recorded as due to cholera, but Parish records do list in the normal graveyard, three burials of members of the Clark family within a space of 5 days. Board of Health records confirms that they were being treated for the disease by Richard Thursfield immediately before the burials. Accordingly, the number of deaths due to cholera is at least 40. However, the suggestions by Randall that “the plague swept away hundreds if not thousands in Broseley and the neighbourhood” is probably an exaggeration.

The known burials in the Cholera Field makes a sad listing of multiple members of families, several of which are well known in the history of Broseley and Jackfield. In alphabetical order and showing the age of the victims, these were:

1832. Samuel Beaman (60), Mary Bullock (4), James Davies (13), John Davies (62), Martha Hartshorne (1), John Kinsell (53), Thomas Pickering (57), Rebecca Pugh (50), John Roberts (8), Margaret Roberts (45), William Roberts (47), Roden Rowley (6), Mary Ann Rushton (2), Mary Ann Rushton (30), Benjamin Wild (64).

1834. John Ager (56), Marie Ager (6), Jane Aston (25), Adam Ball (43), Edward Blower (50), Mary Boden (38), Thomas Crump (35), Bernard Currigan (40), Elizabeth Hall (31), Elizabeth Hartshorne (38), Alexander Hartshorne (45), Lavinia Jones (13), Nichola Hase (66), Ann Lloyd (35), Sarah Lloyd (66), George Love (12), Maria Love (20), Charles Parker (16), Thomas Parker (40), William Reynolds (50), Mary Shaw (76), Ann Weaver (65).

”

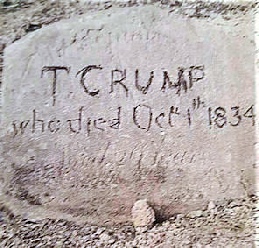

While some reports suggest that the Bishop of Hereford consecrated these graves, this cannot be confirmed by the Bishop’s Register and it is most likely that the burials are on unconsecrated land. The graves were initially surrounded by railings, but vandalised many years ago. Originally, only flat stones level with the soil surface were permitted. The only one known to exist was to Thomas

Crump. The name and date scratched with an improvised tool on the stone says a thousand words about the tragedy felt by grieving relatives at that time

Original memorial stone to Thomas Crump

Today, the site is marked by one erect headstone, sympathetically restored and protected on private land as the land designated on the Tithe map is now bisected by a substantial steel fence.

Present-

The Crump family were significant contributors to the church in Broseley including one Henry Crump, a churchwarden at St Leonard’s Church, who died in 1800, possibly father or grandfather of Thomas.

Cholera victims also do not escape old stories in Broseley. One is that brandy would keep the illness at bay and apparently one person, comatose from its excesses but thought to be dead, was inadvertently placed in a coffin and it was only the noise of earth falling on it which aroused him -

Original memorial stone to Thomas Crump

Originally, only flat memorial stones level with the soil surface were permitted and the only one known to exist was to Thomas Crump. The name and date scratched with an improvised tool on the stone says a thousand words about the tragedy felt by grieving relatives at that time. The graves were known to be surrounded by railings which were vandalised many years ago. Prior to that, Board of Health records in January 1833 shown that an oak timber fence was erected around the burial ground.

Today, the site is marked by one erect headstone, sympathetically restored and protected on private land as the land designated on the Tithe map is now bisected by a substantial steel fence.

While some reports suggest that the Bishop of Hereford consecrated these graves, this cannot be confirmed by the Bishop’s Register and it is most likely that the burials are on unconsecrated land.

Cholera victims also do not escape old stories in Broseley. One is that brandy would keep the illness at bay and apparently one person, comatose from its excesses and thought to be dead, was inadvertently placed in a coffin. It was only the noise of earth falling on it which aroused him -

The spread of cholera was not formally related to contaminated water and food until 1854, by a Dr Snow in England. The work of George Pritchard and others in Broseley to develop clean water supplies suggests that this cause was already considered likely, together with the appalling living conditions. As is well-

Present-