THE NEW WILLEY IRONWORKS: A REAPPRAISAL OF THE SITE

By Ralph Pee

The chief significance of the recent finds at the site of the New Willey Ironworks is that they have revived interest in this almost forgotten but important works. Some details of its documentary history have already been published in this journal[1] , but little has been published or is indeed even known of the physical layout. Unlike the ironworks at Bersham, no picture has survived. Fortunately, the area has not been developed, and by using the scanty documentary and visual evidence available it is possible to suggest a few details of the original plan.

John Wilkinson closed, or gave up, the works in 1804; but they were carried on, possibly as a foundry, by the Foresters until at least 1821[2], and are shown on Baugh’s map of 1808 as Willey Furnace. By 1827 all traces of the works as such seem to have disappeared. They are not shown on C. & J. Greenwood’s map of that year. The remaining buildings, substantially as they are today, are shown on the 1840 Tithe maps as dwellings. The name ‘Willey Furnace’ reappears on the 1882 Ordnance Survey map because, by that time, Willey Furnace had been designated as the postal address of the area.

Until 1775, an outstanding feature of an 18th century ironworks was the water supply and storage system. The arrangements made for the storage of water at New Willey were, to say the least, unusual.

There were four pools, two on the Dean Brook itself and two on a tributary. The largest, near the Lodge Farm, was not as large as any on the Old Wiley site and the one above this, now obliterated, seems to have been quite small. The two on the tributary, one each side the Barrow Road (these are not those which can be seen to-day near the works), could almost be called tiny. A most unusual feature is that the nearest is rather more than a quarter of a mile from the furnace. No attempt seems to have been made to make use of the sizeable tributary coming from the Deer Leap area, or of a not insignificant supply coming from the southwest.

Ignoring the present pools near the works, which can be shown to be incidental, of no use for the purpose, and which are not shown on any early map, there is no trace or record of a mill pond or ‘header tank’ near the works which could have been used to supply water to power a reasonably sized water wheel. It is just possible that water could have been taken by pipes, or very long leets, from each pair of storage ponds to power a water wheel, but there is no sign of any such like arrangement. We know that the Linley Brook, even with its chain of very large storage ponds, was insufficient to power the Old Willey furnace in dry spells[3], yet here on a smaller brook not only is the water storage system on a much smaller scale but no effort seems to have been made to use all available supplies. Furthermore, as far as can be seen, no natural head of water was provided anywhere near the furnace.

If this is correct, the writer can only suggest that the works were designed to rely entirely on steam power by pumping water from some kind of tank or well over a water wheel, and so back to the tank - a sort of closed circuit water system. The limited water storage facilities provided were presumably considered necessary to make up for losses and to provide water for other purposes. It would be reasonable to suppose that the water would be pumped into some kind of elevated reservoir before passing over the wheel but, perhaps not surprisingly, no trace of any such arrangement can be seen today.

(Note : At this time the steam engine was not rotatory and could only be used to pump water, while the rotary motion to operate the bellows of a blast furnace could only be economically provided by using a water wheel. To apply steam power to a blast furnace, the steam engine was used to pump water over the wheel.)

Although possibly an advanced example of its kind, such a system would not have been entirely new. In fact, a growing confidence in steam power can be clearly seen in the arrangements made for blowing furnaces built in the area between 1755 and 1759. At Coalbrookdale, built to operate on a good natural head of water, horse and later steam driven pumps were used when necessary to return water to the storage pond from as early as 1753[4]. At Horsehay (1775), Ketley (1757), and Lightmoor (1758), where the natural water supplies were quite inadequate, steam driven pumps backed by large storage ponds, were provided when the works were built[5].

At the Madeley Wood (Bedlam) furnaces (erected 1757-58), where the natural head of water was insignificant, the water wheels were of necessity driven by water pumped from the Severn and dependence on steam power was complete[6]. At New Willey (1758—59) this development appears to have been carried a stage further and the possibility of making any use of a natural head of water rejected in favour of a head of water provided entirely by steam power.

This possible explanation of the unusual water storage system at New Willey may well be refuted by future discoveries, but it is difficult to see how a worthwhile natural head of water could have been provided from the Dean Brook and its tributaries, without extensive earthworks, which would have been visible today.

It is interesting to note that in 1757 Isaac Wilkinson patented a type of iron bellows, which could be worked by a natural, or steam pumped head of water. In 1759 he was in partnership with Edward Blakeway and others to install his iron bellows at Merthyr furnace, Dowlais, where the installation was a great success [7]. Edward Blakeway, a Shrewsbury draper, was also a partner in the New Willey Company, but so far we have no record of iron bellows being used at the New Willey Ironworks until the Watt blowing engine was installed in 1775.

Because it would be required at the coking hearths and furnace head, it is probable that most of the iron ore and coal for the furnace was brought down the valley leading from the Benthall area by packhorse. The 1882 map shows two tracks from this area, one reaching the Barrow Road near the Round House and works entrance, while the other reaches the road nearer Broseley. There is now little or no trace of the track to the Round House; but the course of the second track is still clearly visible and has been shown by excavation to have been a well worn pack horse track and not, as was thought, the track of a railway[8]. This track probably continued across the valley, outside the main works area, to approach the coking hearths and furnaces head from the N.E. of the furnace where there is a much easier climb to the coking hearth level. The short culvert, still to be seen near the bend in the brook, may have been built to carry this track.

There were two routes from the works to the river for the despatch of finished products and to bring in supplies, one via Swinbatch and Tarbatch Dingle to Willey wharf [9], and one by way of the Benthall rails to wharfs near where the Iron Bridge now stands[10]. Parts of the graded route over the river terrace to Tarbatch are still to be seen between the works entrance to just beyond the Bridgnorth Road. A gate in the field and a track on the map of 1882 indicates where the railway, which followed this route, entered the works. The track of the rails to Benthall would almost certainly have followed the track shown on the same map, which joins the road near the works entrance.

The exact site of the furnace is still marked by a depression at the top of a steep part of the south bank of the valley, but is only marked on the map of 1882 by a bend in the boundary of the field. To the west of the furnace the valley narrows so that the ground rises from the area in front of the furnace to the area now occupied by the rifle range. The building now known as Wilkinson House, about 50 yards to the N.W. of and in front of the furnace, is built into this rising ground so that the front, facing upstream, is two storey while the back is three storey. Looking at the back, the ground floor or basement is now garages, etc., but may at some time have been part of the living accommodation.

Recently a cannon ball was found in front of the house, just below ground floor level. It was found in a layer of black earth overlying virgin clay, indicating a works floor level. This working level, rising from the front of the furnace, apparently extended as far as the rifle range where traces were visible when the range was excavated some years ago. As it is most unlikely that a working level, running round the house and below the level of the ground floor, would have been established after the house was built, this and other factors indicate that the house was not built until the works had been in operation for some time-that is, not earlier than 1760.

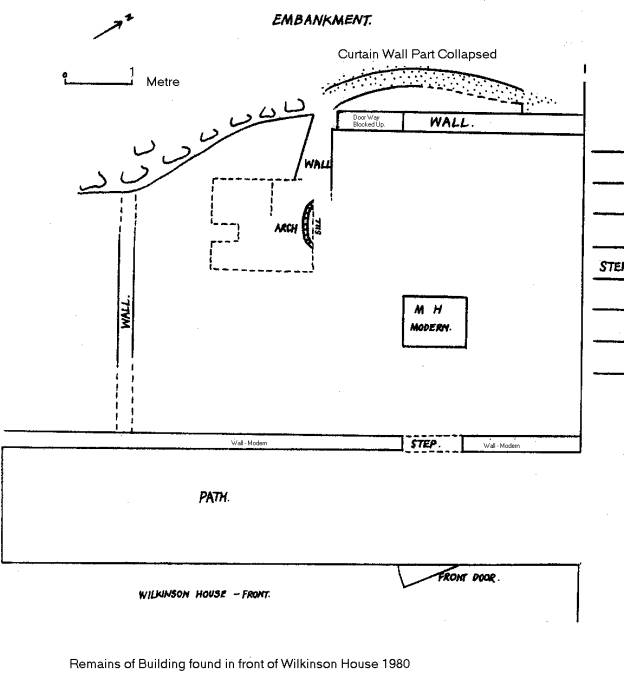

Immediately in front of the house, the ground rises very steeply almost to roof level, to form the high embankment built to carry the coach road about 1790. It was in this embankment, also in front of the house, that the remains of a small building were found. This building, of which only two short walls remained, was at least 11 feet square and may have been larger. This floor, unexcavated, was apparently on the same level as that indicated by the cannon ball. The wall now retaining the embankment had been protected by a rough single brick curtain wall, and a small doorway, thereby made useless, had been bricked up. The door was missing but one hinge pin was still in place and the remains of a wrought iron strap hinge was found. The building had a curious arched extension about 5ft. square at one end and had been white washed inside. The original use of this building can only be a matter of speculation. It obviously pre-dated the embankment and the house, but was in use and deemed worthy of protection when the embankment was built. The whitewash and the extension suggest a conversion to domestic use, possibly as a bake-house, but it is not shown on the O.S. map of 1882.

The original purpose of the main building, Wilkinson House, is also still unknown. It was certainly not built before the works were opened but it can only be assumed that it was a works building built while the works were in operation. The only ground for such an assumption is that it is difficult to see any other reason for such a building in such a remote spot. It is now a very substantial two-storey dwelling with an open basement. It is shown on the 1840 Tithe maps as ‘House and Garden’ but on the 1882 O.S. map as two dwellings and was used as such until quite recently. If built during the period when the works were in operation, so near the furnace and, worse, so near the coking hearths, it can hardly have been built as a ‘desirable residence’. It could have been built to house the first Watt engine and blowing mechanism (1775), and if so is of considerable historical significance. Engine houses of that time were, however, usually small and simple. This is a large building with an elaborate cruciform roof. Also, for a blowing engine house, it is a long way from the furnace.

On the other hand, there are traces of a large arch, which could have been a ‘Bob Arch’ for a beam engine in the rear wall, and another, not so clear, in the wall facing the coking hearth. The unusual distance from the furnace could have been provided to accommodate the ‘Water Bellies’, which were built at the time to smooth out the blast from the single cylinder Watt blowing mechanism [11]. Finally, if it was not built to house the Watt blowing engine, what was it built for ? All that we can say at present is that it was built some time after the works were opened and may have been built to house the first Watt blowing engine. Although it seemed unfortunate at the time, it is understandable that Mr. Keith Gale, acting as adviser to the Department of the Environment when the property was sold some years ago, could not see his way clear to recommending its protection as a national monument. It is of course a scheduled building and we are lucky that the present owner is interested in its historical significance.

The crenellated Round House was clearly built as an estate lodge, and the small buildings shown nearby on the O.S. map of 1882, and of which traces still remain, would have been keepers’ kennels, pigsties and the like. The Round House pre-dates the coach road, as the ground round it has obviously been raised to take this road. It is unlikely that the road to the hall from this lodge followed the same route as the coach road, since before the very high embankment in front of Wilkinson House was built the climb out of the valley there would have been very steep. The estate road is more likely to have followed an easier route to the right. The house is shown as a ‘Toll House’ on the 1827 and 1840 maps, and it may be that the coach road to Bridgnorth via Dean Corner and Wiley crossed the valley at this point to enable it to be used as a toll house.

The very small building opposite the Round House, known locally as The Weigh House, seems to have marked the works entrance. The window or hatch faced the road to the works while the door faced the Barrow Road. It had a fireplace and, although it was originally crenellated to match the Round House[12], appears to have been built for works purposes.

The four Willey Furnace Cottages, shown on the 1882 O.S. map and of which two remain, are, like Wilkinson House, split level but in this case merely because the coach road embankment has encroached on one side. On the 1840 Tithe maps, (maps, because the row straddles the parish boundary), the three cottages on the Broseley map are shown as ‘House and Garden, also shops under occupation of one John Wilkinson’. The cottage on the Willey map, nearest the furnace, is shown to be in the occupation of a Sarah Wilkinson. The 1851 census return informs us that at that time Sarah Wilkinson, a widow aged 74, ‘Blacksmith Trade’, with two sons John and Francis, also ‘Blacksmith Trade’, were of Willey Furnace and that they employed three others, two Garbetts, nephews, and an apprentice. (A Mr. W.D. Wilkinson of Sutton Coldfield, a descendent of Isaac Wilkinson’ a brother, is a member of our society).

The two cottages still standing are substantially built and much wider than normal cottages of the period. Their general appearance and the ‘shop under’ of the Tithe maps suggests that they were not originally built as cottages but as works buildings, possibly pattern shops. A very similar row of buildings the pattern shops of Onions foundry in Broseley, were also converted into cottages when the works closed. If the Willey Furnace cottages were originally works buildings, no company-built cottages were provided in the Willey Furnace area. In very dry weather traces can be seen of a row of buildings opposite the cottages. These were presumably works buildings demolished when the works closed. They were not shown on the 1840 Tithe maps.

Besides producing cast iron and cast iron objects, the New Wiley Ironworks was equipped to bore cannon, steam engine cylinders, pumps, etc., and to produce bar iron. There were three Watt engines. This means that the works must have been quite extensive and probably covered most of the area bounded by the Dean Brook and the steep side of the valley. This area does in fact show signs of having been occupied. The complete disappearance of the works as such between 1821, or later, and 1827 is remarkable and it is noticeable that the 1882 O.S. map, which shows domestic buildings and remains in great detail, shows no trace whatever of other buildings.

It is doubtful if we shall ever have a complete picture of the New Willey Ironworks, but it does provide a fascinating line of research.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Miss Anne Turner for a tracing of the 1882 O.S. map and to Mrs. Marilyn Carter for the fair copy of my mutilated reproduction. Information from the Tithe maps and census returns is the result of the not inconsiderable labours of Mrs. Veronica West and Mrs. Susan Perfect. Thanks are also due to Mike and Joan Banks of Wilkinson House for bringing to my notice the happy results of their gardening activities. The drawing of the remains uncovered was prepared by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.